When you boil it all down, the first and primary task of software development is problem analysis. Although many people commonly view software development as the process of defining requirements and specifications, writing code and testing it, if the problem to be solved has not been correctly defined, the wrong solution will be delivered. Perhaps this helps to explain the high rate of software project failures.

When you boil it all down, the first and primary task of software development is problem analysis. Although many people commonly view software development as the process of defining requirements and specifications, writing code and testing it, if the problem to be solved has not been correctly defined, the wrong solution will be delivered. Perhaps this helps to explain the high rate of software project failures.

I was thinking about comparisons of the software industry to the building industry and the question came to mind, "How many times do you see the wrong building built?" At first, I thought "Never. Builders build what they are told to build."

Then I thought about a building I drive past about once a week. It’s been finished for over a year, a nice looking industrial-type building in an industrial part of the city, but still for sale and standing vacant. I have verbalized on more than one occasion, "Why would anyone build such a large building without someone to buy it?"

It appears that someone thought there was a problem that needed to be solved by building another building. However, the market seems to be indicating that the problem or need didn’t really exist. So I guess that is an example that software developers are not alone in building systems that meet a need that doesn’t exist.

I think it’s important to understand that needs and problems are transitory. Today’s problem may not be so next week! Therefore, we must consider taking the longer view when we think about what really is the problem at hand. Problems are also opportunities in disguise. Just consider that most innovations were born out of the necessity of solving a problem.

If all of this is not confusing enough, there are times when trying to address a problem too quickly is worse than taking no action at all. And even more vexing is failing to react to problems quickly enough to prevent further damage! This leads us to ask questions such as , "When does putting out fires shift from necessity to habit?" and "When is a problem truly an emergency instead of a ‘perceived crisis’?" Within t his context, we can view the high-level software development process as:

1. Problem analysis

2. Requirements definition and refinement

3. Software specifications and detailed design

4. Software creation and refinement

5. Software validation

These are often not performed in sequential order, but rather in cycles where things are learned in the process of performing the steps. However, the problem analysis step is where much of the learning needs to occur and learning more about the problem later often results in painful changes and project problems. To embark upon requirements definition too early is human nature, but it also causes problems later in the project that are difficult and costly to resolve. We software people are often guilty of "just trying to get the job done" at the expense of first understanding what the job is.

What is Problem Analysis?

Problem analysis is the process of understanding and defining the problem to be solved. Problem analysis is not problem solving! Problem solving identifies solutions that conform to the needs and constrains of the problem. It is common to propose a solution too early that does not consider the restrictions and possible shortcuts associated with the problem. When these things are overlooked, we either have an incomplete or excessive solution.

Five Step Process For Problem Analysis

Much of what is done in designing and building information systems is to solve problems, even though the objective of the system may be seen as improving existing systems or taking advantage of market opportunities. The basic motivation of people to buy or build something is to meet a need. Needs arise most often from problems. Therefore, a big part of defining requirements is to understand the problem so that the right solution can be delivered. The following process is very helpful in defining, understanding and solving problems. We will go through each of the following steps in detail in the rest of this module.

Step 1 - Define the Problem

This is the first and foremost concern. If we can’t state the problem, we can’t even know where to begin in solving it. This can be one of the most difficult parts of any project and the most important. An amusing, yet sad, example of this was when a group of diplomats spent three days at the outset of an international summit debating over the size and shape of the meeting table. Likewise, when we can’t get a clear view of the problem, we can get easily distracted by all sorts of side issues.

Defining the problem is easier said than done because people have different views of what the problem really is. Here are some tips to help define the problem:

-

Put the problem in writing

Stating the problem in writing firmly documents it for a common and firm understanding among a group of people. When defining a problem in writing, standardized processes help greatly to achieve consistency and completeness.

-

Get multiple perspectives

In viewing a particular problem, people will have differing views of the problem depending on the individual person’s background and perspective. If you miss a perspective, you may miss an important angle of understanding an important aspect of the problem.

-

Look for deeper problems

In some cases, the problem that is most obvious is only the tip of the iceberg. The deeper problems may be the contributing causes to the effect that the main problem is manifesting.

Step 2 - Understand the Root Causes

Each problem has one or more root causes. Many times, the problem being seen is the result of the root causes, and is therefore a symptom, but not the core problem. In gaining an understanding of the root causes, you are asking "What’s the problem behind the problem?" To identify the problems behind the problem, a Root Cause Analysis is performed. In the Root Cause Analysis, questions are asked, such as:

-

What is the primary problem?

This goes back to the problem that should have been stated in writing from the previous step. This question verifies that the primary problem can be described accurately and completely.

-

What are the contributing factors?

The contributing factors are things below the surface that have a role in the problem. The impact of the contributing factors will vary by item, but once the factors are identified, a greater understanding of the problem is gained.

-

Who knows about the problem?

This identifies the people who may be available to provide additional insight to the problem.

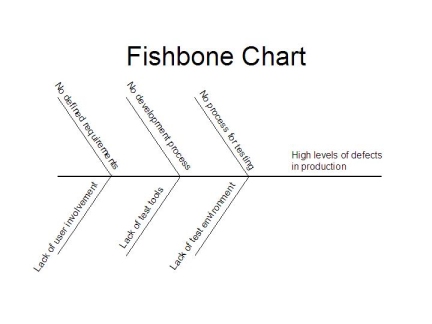

Figure 1 - A Fishbone Chart

A tried and true way to describe root causes is to use what is known as a "fishbone chart." Each contributing factor is shown as a branch off of the main problem. Fishbone charts are easy to draw and work well as ways to drive a brainstorming session.

Step 3 - Identify the Affected People

Each problem will impact a given group of people. Each of these people will likely have different needs and concerns, which need to be considered in the solution. These people are known as a "stakeholders." The stake could be positive or negative. For example, the person could have a positive stake in seeing a problem resolved because their work would be made easier. Another person could have a negative stake in seeing a problem resolved because it gives them job security in constantly fixing the effects of the problem. The possibilities of affected people include:

-

The project sponsor

This is the person that initiates and pays for the solution.

-

Customer

This is the person that is served by the solution.

-

User

This is the person that has to apply or use the solution.

-

Management

This is the group that controls the solution.

Step 4 - Define the Scope of the Solution

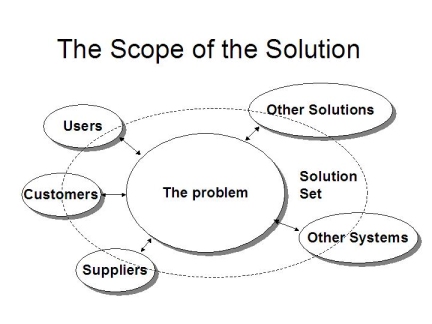

The scope of the solution forms the boundary you will need to work within to solve the problem. The scope of the solution addresses the things, which are within your control to address. It is important to define the scope of the solution so that you do not overstep the boundaries of what you can reasonably fix. There are two perspectives of a solution:

Internal, which focuses on the problem to the solved from our perspective as the product or service provider.

Figure 2 - The Scope of the Solution

External, which focuses on the people or things that interact from the outside, such as:

-

Customers

-

Suppliers

-

Users

Each of these perspectives will have unique considerations and needs to be seen in the solution of the problem. There is only so much you have control over to affect a solution. These boundaries will form the scope of the solution. To solve the problem, to have to work within this scope and perhaps get cooperation from people outside of this scope to address the issues that are out of your control.

You define the scope of the problem by considering the affected areas and specifying which things you can reasonably and effectively address.

Prioritize, Prioritize, Prioritize!

In this step, the problem can be prioritized based on severity and potential impact. Potential impact underscore the fact that a problem may not be seen as urgent or important today, yet may have the risk of manifesting as a major problem in the future. Wisdom is required at this point to distinguish between borrowing trouble needlessly and planning wisely.

Practical Guidelines, Please!!!

Okay, I know this all gets very philosophical at times, so here are some questions I have found helpful in the past to help distinguish between the urgent and the important:

The important:

-

Does it affect the safety and well-being of people?

-

Will the company lose money because of it?

-

Will we be breaking the law because of it?

-

Will the organization be at risk of legal action because of it?

-

Will we lose an important window of opportunity because of it?

-

Will solving this problem make a positive difference in the long-term?

-

Is the problem adversely affecting the welfare and attitude of the organization?

If any of the answers to the above questions are "yes", then you likely have an important problem to solve and should devote immediate attention to it?

The urgent:

-

Is there a dictate from senior management to address this by a particular date?

-

Are people unsure why a particular target completion date was set?

-

Is this a concern to just a few people, even one?

-

Have we dealt with a similar problem recently without a satisfactory solution?

-

Is this a recurring problem?

-

Is management unwilling to enact a permanent solution?

-

Are members of management in conflict over the problem and/or the solution?

If any of the answers to the above questions are "yes", then you likely have an urgent problem which may be overshadowing other more important issues. To attempt a solution may please management, but will likely not address the core issues. You will likely have the same problem again in a slightly different form atsome point in the near future. In fact, these is a strong likelihood that if you ignore this problem it will either go away or mutate into another one with the same false sense of urgency.

Step 5 - Identify Solution Constraints

There will often be barriers to solving the problem. Once identified, the barriers can be addressed instead of ignored. A constraint is a know lack of something, an inhibitor. Constraints can be seen as:

-

A lack of time to complete the solution

-

The lack of money to perform the solution

-

A lack of people to work on the solution

-

The lack of a technology to give you leverage in solving the problem

-

Political problems which inhibit people from cooperating in solving the problem

-

Environmental problems, which inhibit a solution due to the nature of the business, technical environment, geographic environment, etc.

Once the solution constraints are known, they can be addressed. It is common to see only a partial relief of constraints. In fact, sometimes no matter what you do, the constraints are out of your hands and you just have to figure out a way to work around them. As I have been known to tell my test teams, "When the going gets tough, the lazy get creative."

Conclusion

This brief article only scratches the surface in what it takes to understand the problem to be solved. There have been many books written on the topic, but experience is often the best teacher. If you don’t already have a mentor, find someone who has some gray hair and is good at solving problems and watch them in action as they work to identify the real problem and set priorities. Be warned, however, these people are in a very small minority.

Based on what I’ve seen in many companies, I would look outside of the IT organization and perhaps, even outside of a corporation. I know that in some ways this article may be frustrating to those who are looking for ways to solve problems right away, but I hope this article has given you a new or greater appreciation of analysis before solution. I would like to hear about your experiences and ideas in problem analysis. Feel free to write me at from the contact page.

Checklist for Problem Analysis

1. Is there a standard for problem definition in your organization?

2. Has the problem been described in writing?

3. Has the problem been reviewed by people who are knowledgeable about it?

4. Has a root cause analysis been performed?

5. If so, were the appropriate people involved in the analysis?

6. Has a standard set of context-free questions been developed for your organization?

7. Have context-free questions been asked about this particular problem?

8. Have all the appropriate people been queried?

9. Have the context -free questions been answered to your satisfaction?

10. Have false assumptions been identified?

11. Has the scope of the problem been determined?

12. Have the affected people been identified?

-

Internal

-

Sponsors

-

Users

-

Technical people

-

Project managers

-

User management

-

-

External

-

Customers

-

Users

-

Suppliers

-

13. Has the scope of the solution been defined?

-

Internal

-

External

14. Have constraints to the solution been defined?

-

Time

-

People

-

Money

-

Politics

-

Technology

-

Environment

15. Have modeling techniques been used to graphically understand the process or product described?

-

UML

-

E-R models

-

Data Models

-

Process flows

Resources for Problem Analysis

Are Your Lights On? By Gerald Weinberg

Problem Frames and Methods: Structuring and Analyzing Software Development Problems By Michael Jackson

Root Cause Analysis : Simplified Tools andTechniques By Bjorn Andersen (Editor), Tom Fagerhaug, Bjorn Anderson, Birn Andersen

Root Cause Analysis: Improving Performance forBottom Line Results By Robert J. Latino, Kenneth C. Latino

Apollo Root Cause Analysis - A New Way Of Thinking By Dean L. Gano

The Root Cause Analysis Handbook -A Simplified Approach to Identifying, Correcting, and Reporting Workplace Errors By Max Ammerman